1. Why Porosity and Oxygen Content Matter More Than Most Engineers Realize

Most engineering discussions about NdFeB magnets revolve around grade (N35–N55), operating temperature, geometry, or coatings. Rarely do buyers or designers ask the most fundamental question: what is the internal quality of the magnet itself? The real long-term reliability of an NdFeB magnet is determined not by the coating thickness or the grade number, but by how dense, how porous, and how oxygen-contaminated the magnet’s microstructure is.

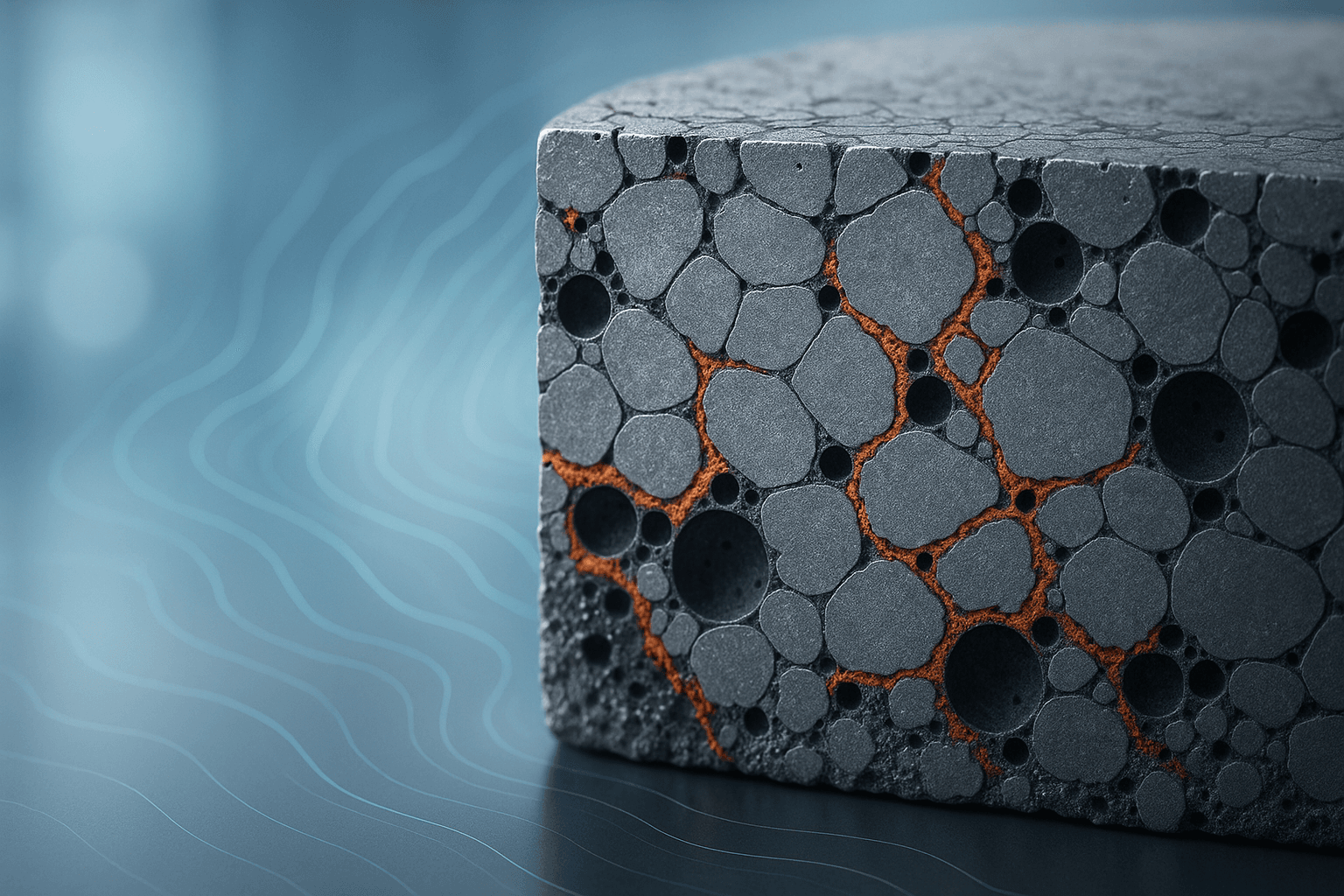

Sintered NdFeB magnets are made from fine alloy powders compacted and vacuum-sintered into dense polycrystalline blocks. But no matter how advanced the process is, sintering cannot eliminate all voids. Small gaps remain between grains, grain boundaries, and within imperfectly fused regions. These pores act as stress concentrators, moisture channels, chemical reaction sites, and magnetic discontinuities.

Magnets with excessive porosity behave like brittle ceramic sponges: they crack more easily, absorb moisture more rapidly, corrode faster under coatings, and lose magnetic performance more quickly under heat and vibration. Density and oxygen content together create a profile of internal stability—and this profile dictates how a magnet will age in a motor, a sensor, a robot joint, or an outdoor device.

The difficulty is that porosity and oxygen levels are invisible to end users. A low-density, oxygen-heavy magnet can look shiny, clean, and well-coated. It may even pass a short salt spray test. But internally, it is a hazard waiting for moisture, stress, or temperature cycling to expose its weakness.

Porosity and oxygen do not merely correlate with lifespan—they define it.

2. How Porosity Forms Inside NdFeB Magnets—and Why It’s So Dangerous

Porosity forms during the powder metallurgy process. NdFeB powders are pressed under high load, then sintered at temperatures near 1000–1100°C. During sintering, the powder particles shrink and fuse together, but they never achieve 100% theoretical density. Microvoids remain in the structure, and their distribution depends heavily on powder quality, pressing uniformity, oxygen control, and vacuum sintering conditions.

2.1 Types of porosity inside magnets

Several distinct forms of porosity influence performance:

- Intergranular pores between Nd₂Fe₁₄B grains

- Closed pores inside grains

- Open pores linked to surface defects or machining

- Elongated pores created from uneven pressing

- Oxygen-enriched pores where Nd-rich phases oxidize

Each type affects reliability differently, but all reduce structural and magnetic continuity.

2.2 Density as a measure of porosity

Theoretical density of Nd₂Fe₁₄B is ~7.6 g/cm³.

Real magnets range from:

- 7.50–7.60 g/cm³ → high-density, low-porosity, premium

- 7.30–7.45 g/cm³ → typical industrial quality

- 7.10–7.25 g/cm³ → low-density, high-porosity, short-life magnets

Every 0.05 g/cm³ drop corresponds to a significant increase in void volume.

2.3 Why porosity acts like internal cracks

Pores behave like pre-made microcracks. They concentrate mechanical stress, especially in:

- High-rpm motors

- Linear actuators

- Robotic joints

- Magnetic couplings

- Press-fit housings

A porous magnet requires far less force to crack than a dense one. Even moderate vibration can propagate cracks through connected pore networks.

2.4 Porosity as a corrosion accelerator

Pores absorb:

- Moisture

- Oxygen

- Chloride ions

- Industrial gases

- Cleaning solutions

A pore-filled magnet corrodes:

- Faster

- Deeper

- Under coatings

- Even when seals appear visually intact

Many engineers mistakenly blame coating failure for corrosion problems, while the real cause is poor substrate porosity.

2.5 Why coatings cannot fully compensate for porosity

Nickel plating does not fill pores reliably. Epoxy can fill some surface-level voids, but deep pores remain unprotected. Parylene performs better but still depends on surface cohesion and grain-boundary strength.

If the substrate is porous and oxygen-rich:

- Coatings adhere poorly

- Blistering occurs earlier

- Moisture penetrates faster

- Underfilm corrosion spreads more quickly

Substrate quality, not coating, determines the ceiling of corrosion resistance.

3. The Hidden Influence of Oxygen Content on Magnet Integrity, Corrosion, and Aging

If porosity is the “volume problem” inside NdFeB, oxygen is the “chemical problem.” Rare-earth elements in NdFeB, especially neodymium, bond strongly with oxygen. During powder milling, pressing, sintering, or machining, oxygen can enter the structure at surprising levels.

3.1 Typical oxygen levels

- 800–1200 ppm: high-quality, controlled atmosphere magnets

- 1500–2500 ppm: average commercial magnets

- 3000–4000+ ppm: low-quality magnets with fragile grain boundaries

These numbers matter more than most buyers realize.

3.2 How oxygen weakens magnets

Oxygen reacts with Nd-rich grain boundary phases to form Nd-oxide, which is:

- Brittle

- Nonmagnetic

- Chemically unstable

- Easily hydrated

- Prone to expansion when exposed to humidity

Oxygen-rich grain boundaries lose mechanical cohesion, making the magnet more susceptible to:

- Chipping

- Cracking

- Fracture propagation

- Poor coating adhesion

3.3 Oxygen as a catalyst for magnetic aging

Magnetic domains rely on well-bonded grain boundaries. Oxygen-rich boundaries cause:

- Lower coercivity

- Higher magnetic decay at elevated temperatures

- Faster aging loss even at room temperature

- Flux instability in sensors and precision devices

In motors or encoders, such deterioration can cause detectable performance loss.

3.4 Oxygen and porosity combine into the worst-case scenario

A porous magnet with high oxygen content behaves like a sponge filled with reactive chemicals. Moisture enters the pores, reacts with oxygen-rich areas, generates hydrogen, and causes internal swelling. This stress delaminates coatings from below and fractures the magnet.

No coating can stop this.

Only a high-density, low-oxygen substrate can.

4. Real-World Implications: Why Density and Oxygen Define Long-Term Reliability

Porosity and oxygen content determine how magnets behave in the environments where they are actually used—motors, robots, sensors, EV components, and outdoor assemblies. Below are the real engineering consequences.

4.1 Mechanical reliability under high speed and vibration

At high rotational speeds, centrifugal force increases with the square of rpm. Porous magnets crack far earlier than dense magnets. Even a tiny internal pore becomes the seed of catastrophic failure at 30,000–60,000 rpm. Drone rotors, BLDC motors, and servo drives suffer the most.

4.2 Corrosion resistance under humidity and salt spray

Porous + oxygen-rich magnets fail:

- Earlier

- Faster

- More deeply

- Even under “good” coatings

Low-porosity magnets can run for years under the same conditions.

4.3 Coating lifetime

Coatings on dense substrates:

- Adhere better

- Resist blistering

- Survive thermal shock

- Maintain continuity

- Provide long-term passivation

Coatings on porous substrates behave unpredictably.

4.4 Magnetic stability

Low-density and oxygen-rich magnets show:

- Higher initial variation

- Faster magnetic decay

- Reduced flux density over time

- Poorer performance in sensors

- Lower coercivity at elevated temperatures

Applications requiring precision—encoders, medical sensors, robotic joints—suffer most.

4.5 Thermal shock and thermal cycling

During rapid temperature changes:

- Porous magnets expand unevenly

- Oxygen-rich boundaries crack

- Stress accumulates at pores

- Coatings delaminate

Dense magnets tolerate heat cycles significantly better.

Conclusion: Why Magnetstek Focuses on Low Porosity and Low Oxygen for Premium Reliability

Porosity and oxygen content are the invisible foundations of magnet performance. Coatings, grades, shapes, and magnetization patterns matter, but they cannot overcome a weak substrate. Magnetstek ensures magnet reliability through:

- High-density sintering

- Strict oxygen control during powder handling

- Advanced particle milling atmospheres

- Vacuum sintering technology

- Grain-boundary engineering

- Post-sintering densification

- Optimized surface preparation before coating

The result is NdFeB magnets with:

- Higher mechanical strength

- Greater corrosion resistance

- Improved coating adhesion

- Better high-speed performance

- Lower magnetic aging loss

- Longer operational life

When applications demand true reliability—motors, robots, sensors, aerospace components, outdoor systems—microstructure is everything.

Magnetstek builds magnets from the inside out.